Watch Your Language: Part Four

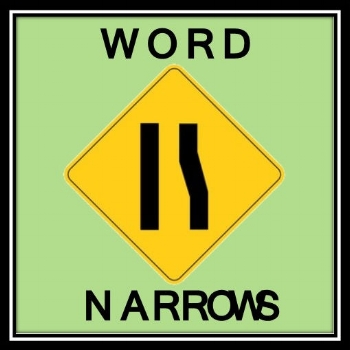

Like a freeway losing a lane, a word can narrow. Its meaning can contract and taper down. Somewhere along the line, that happened to the word worship. For many Christians, it has come to mean almost the same thing as singing to God in a church meeting: “After worship, the pastor spoke.” Or when we say worship, we may mean the meeting itself: “We worship at 10:45 a.m.”

Worship: Its Meaning Matters

Because we so often hear worship used to mean music or meeting, we may ask: Does that even matter? It does, because we can easily read those narrowed meanings back into the Bible, our standard for what we believe and do. The New Testament mentions singing and music perhaps a half-dozen times in connection with Christians gathering. But—and this may come as a surprise—the word worship does not appear in those verses. Nor does the New Testament say worship is the reason for meeting together.

Can we worship through singing? Yes. Should worship take place when we meet? Of course. But the New Testament does not confine worship to the gathered church. Biblical worship also extends into every corner of our involvement in the scattered church. If we worship only in gathered-church mode, then worship narrows to only about one percent of our waking hours.

Bible Words for Worship

Four main words in the Greek New Testament sometimes get translated into English as worship. Those words also appear in our Bibles as kneel, bow, (or prostrate), serve, and minister. It follows that worship may take many different forms. For example, the prophets and teachers in the church at Antioch worshiped as they fasted and prayed (Acts 13:1-2). The women at the empty tomb worshiped by holding onto Jesus’ feet (Mt. 28:9). Jacob, says the writer of Hebrews, “worshiped as he leaned on the top of his staff” (Heb. 11:21). None of these examples of worship took place in what we call a church service.

The Old Testament, right from the start, began using a full-width, multi-lane, Hebrew word for worship. The verb AVAD (and its noun AVODAH) are translated as worship, work, and serve. For example:

- God to Moses: “When you have brought the people out of Egypt, you will worship [avad] God on this mountain” (Ex. 3:22).

- “You shall work [avad] six days . . . .” (Ex. 34:21).

- “. . . choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve [avad]. . . . But as for me and my household, we will serve [avad] the Lord" (Josh. 24:15.) (Emphases added.)

To us, work and worship may seem unrelated, as different as land and sea. How, then, can the same Hebrew word describe both? What connects the two? The link is that third meaning of avad: to serve. Both worshiping and working are ways in which we serve God. This means I can offer my daily work—paid or unpaid—to God as service/worship he accepts.

How Can Work be Worship?

“But how,” you may be asking, “can I actually offer my work to God as worship. My work seems so—well—ordinary. So earthly.” True, our culture and perhaps even our church traditions can condition us to think our work has zero spiritual value.

Old Covenant worship centered in the Tabernacle and then in the Temple. There, the people brought animals and cakes made of grain to place on an altar. So the essence of worship back then involved offering sacrifices in a particular place. Because Jesus made the ultimate sacrifice for our sins on the cross, we no longer worship God by bringing him bulls or birds. Today, we worship by offering sacrifices of another kind.

The writer of Hebrews explains: “And do not forget to do good and to share with others, for with such sacrifices God is pleased” (Heb. 13:16). Ponder on that for a moment. Doing good. Sharing with others. Those are “sacrifices.” And such sacrifices “please God.”

Now stop and think about your work—paid or not. Does it help to provide products or services that do good for others? Does it supply you with the means to share with others? In his book, Work: The Meaning of Your Life, Lester DeKoster says, “Work is the form in which we make ourselves useful to others.” And typically, our work actually does require us to sacrifice—giving up our own time, comfort, and pleasure to serve others with what we produce.

Offering Your Body in Worship

Your physical body becomes a major part of New Covenant offering. As Paul urges, “offer the parts of your body to him [God] as instruments of righteousness” (Rom. 6:13). And again, “offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God — this is your spiritual act of worship” (Rom. 12:1). Whatever your work, you do it with your body—hands, brain, feet, eyes, ears, and so on. As your body and all its parts work in faith, hope, and love—doing good and sharing with others—that work becomes your “spiritual act of worship.”

“But wait,” someone may object, “I can’t always be thinking about God while I work. I drive a bus. My mind must focus on my passengers and the traffic around me.” The good news is that offering your work to God as worship does not require you to consciously think or feel excited about him every second. As Jesus told the woman at the well, the Father is looking for those who worship him “in spirit and in truth.” While your work demands the full attention of your mind, your spirit--energized by the Holy Spirit--can continue in unbroken fellowship with God.

Talk about truth that transforms! Suddenly, when you realize you may worship as you work, that narrowed word worship suddenly widens. Work now becomes God’s good gift (click here for brief video). Work is now something to love rather than hate. If we have come to God through faith in Christ, we can stop hating Mondays and start looking forward to them. This lets worship out of its narrow space in a “Sunday box.” Worship on Sunday, yes, and on every other day of the week--including workdays.